This article appeared in the Nov/Dec 2012 issue of Marathon & Beyond

Afterlife

You’ve

Just Completed Your First, Fifth or Fiftieth Marathon.

What

Do You Do Now?

By

Dan Horvath

“Never

again.” If you’re

a marathoner, it’s more than likely that you’ve uttered those

exact two words. Whether you’ve achieved your goals, failed

miserably, or fell somewhere in between, it’s natural to have a

letdown after you finish. This is the case whether you had other

races planned, or hadn’t thought at all about any future running.

There are a few who land on their feet, and can’t wait to start

training for their next one, but for many to most of us, “never

again” is the first thought that occurs to us as we cross that

finish line, at least some of the time. It takes some period of time,

be it hours, days, weeks, or longer, before we begin to think about

what comes next. What comes next is, however, pretty important for

the future of your running career.

This

article first occurred to me when a friend finished her first

marathon, doing quite well in the process, and proceeded to ask me,

“What do I do now?” When I began to think about just how

important the answer is, it occurred to me that this is something

that all of us should consider.

So

this is all about rest and recovery, as well as post-marathon goal

setting and planning. It’s about taking stock of your achievement,

and then striving to improve, or setting some different goals and

developing a plan to achieve them.

So

now that you’ve crossed that finish line, here’s what you need to

do:

Rest

and Recover

This

is job one. No matter how you did during your race. No matter how

soon your next race will be. No matter how you felt during the race.

No matter how you feel once you’ve finished. The marathon has

beaten you up to some extent. You simply must

recover.

If

you ran strong and finished strong, you’ll need some rest, but

perhaps not as much as if you crashed and burned. If your finish,

final miles, or even entire second half conjured thoughts of the

Bataan Death March, you will need to take more time off afterward.

One rule of thumb is to take as many days to recover as there were

miles in your race, so about a month of recovery time is reasonable.

This may, but doesn’t necessarily have to mean, no running for 26

days. You should, however, at least have the attitude that you are in

recovery mode for that length of time. Here are some additional

thoughts about rest and recovery in terms of a timeline.

Within

one hour after your finish:

Walk.

Walking immediately after finishing helps stretch your strained

muscles just a bit, and helps your body to cool down gradually –

a good thing.

Drink.

Most runners will be dehydrated after a race, and need to drink

water or a sport drink afterwards. A smaller percentage of runners

will be in danger of hypnotremia, a dilution of sodium in the

bloodstream and definitely should not

drink afterwards. There is a wealth of information about

hypnotremia that will help you determine whether you may be

susceptible to it.

Eat.

As with any hard endurance effort, your body needs some amount of

carbohydrate and protein as soon as possible in order to begin

rebuilding torn or strained musculature. Eating something within 15

minutes of finishing is recommended, but any calories within the

first hour will be helpful.

Stretch.

But do so very

gently!

This will also help your muscles recover.

Soak.

What if I told you that there’s a way to immediately reduce

inflammation and jump-start recovery of your worn leg-muscles

without using drugs? Soak your legs in water as cold as you can

stand. In 2005, I participated in the Tahoe Triple, three marathons

in three consecutive days around Lake Tahoe. I learned that soaking

one’s legs in the 39F lake water right after each run was de

rigour

to enable recovery for the next day’s big effort. If you can’t

manage to find a body of cold water right after the race, do so as

soon as possible.

Get

massage. These are available in the finish area of many races.

Although these 10-minute variety massages aren’t as thorough as

the one-hour types, they can help smooth out your tired muscles.

Don’t plan on being able to get back off the table easily

afterwards.

Celebrate.

In any way you feel is appropriate. You’ve earned it.

Within

one day after your finish:

Drink.

You will most likely be dehydrated for a while. If you’re not in

danger of hypnotremia, keep right on drinking.

Eat.

You need additional protein and carbohydrates throughout the 24

hours following the race in order to continue rebuilding your

strained muscles. Especially protein.

Walk.

Don’t run, but go for a walk the following day.

Stretch.

But do it gently.

Soak.

Another bath in the evening of the race will also be helpful as

well as soothing. This one doesn’t have to be in cold water!

Within

one week after your finish:

Walk.

Walking will still be helpful in the days following your race.

Stretch.

Stretching will also be helpful in the coming days.

Get

massage. After a couple days, it’s time for a good massage. It’ll

do wonders. You’ll feel human again.

Run.

Yes, unless you’re injured or have time off planned, you can try

to run again. But do it gently. Remember the recovery rule. So no

speedwork or high mileage, thank you. By the time the following

weekend rolls around, depending on how you finished (see above) you

may feel good enough to run hard again. Resist. Yes, you may have

another race scheduled (see below) at some point, but if at all

possible, you should still take it easy.

Cross-train.

Gently. Easy cycling, swimming, even easy strength training will

actually help speed your recovery. It may even help you feel like

you’re not a total slouch (don’t worry: you aren’t anyway –

you deserved that rest).

Within

one month after your finish:

Get

massage. A second one a week or two after the first one will be

helpful as well.

Run.

After a couple weeks you can tentatively begin running hard again.

Cross-train.

You can gradually get back to the levels of these activities that

you were at prior to your race. You’ll likely find that your

fitness in these areas will come back faster than your running.

That’s

what most

of us should

do. What if you have another race in a month, a week, or, for the

truly insane, a day? You should still follow the ideas outlined above

as much as possible. You may just need to temper the ‘within one

month’ plans.

Bear

in mind that you are extremely susceptible to illness and injury and

during this recovery period. Your immune system has been stressed, so

you will not be able to fight off cold, flu, or other infections as

well as before. It’s best to avoid possible contact with sources

for such diseases by taking additional preventative measures.

Likewise, injuries are very common among runners who have recently

completed a marathon and who have begun running again. Your entire

musculoskeletal system has also been stressed and by running too hard

too soon afterwards, you’re at risk of bringing on a new injury.

The

rest and recovery information noted above is about the physiological

aspects of your post-marathon period. Psychological aspects can be

just as important. The initial euphoria may wear off rather quickly,

giving way to a let down, possibly even depression. The marathon,

including the planning, training, and the execution of the event

itself, was a huge part of your life for a long period of time. Now,

suddenly it’s over. As we said right off the bat, what do you do

now? Most importantly, devote the time and effort that you spent

preparing for your marathon on something else that’s important to

you. This may also be running-related, such as volunteering at a race

or concentrating on some other type of event or distance. Or perhaps

some aspect of your life, such as time with the family or friends had

been slightly neglected during your race build-up. Now is the time to

devote more of your time to those parts of your life.

Do

a Post Mortem

You’ve

run a marathon. Even in this day and age when lots of other folks are

doing so, there are still billions who aren’t. It’s a great

accomplishment to complete such an endeavor, no matter how you look

at it. That said, we need to note that we are going to feel much

better about some

of these efforts than others. Someone who reaches a long-standing

goal of, say, qualifying for Boston, breaking three or four hours,

placing well, etc. may be quite ecstatic afterwards. Those who crash

and burn, or otherwise miss a time goal by a little or a lot may not

be quite so happy with their effort. The former group ought to go

ahead and enjoy their celebration, while the latter group should take

solace in the fact that they’ve still accomplished and learned a

great deal. This advice is coming from someone who misses his goals

extremely often.

After

a day or two your head will be relatively clearer and you can be a

bit more objective about your run. This is the time to truly take

stock. Many of us would or should have set three goals for ourselves:

Our

“wildest dream”. A goal that appears just out of our reach but

is not completely out the question for us. For example, placing in

the top three of your age group when the best you’ve done

previously was fifth, or perhaps setting a personal best time even

when this wouldn’t have been indicated by your training. Anything

that exceeds expectations qualifies here.

The

standard doable-but-difficult goal. This can be anything from

winning the race to simply running a steady pace to making a

specific time goal. This is the attainment of exactly what you’ve

trained for.

The

acceptable goal. This is the bare minimum that you will accept,

based on your training and past performances. For most of us, this

should be to simply make it to the finish line. For the

over-achiever/type A/hyper-intense types, it may be a time goal

that’s somewhat slower than the standard-but-difficult time goal.

Now

we can ask, how did we do in terms of these goals? And more

importantly, how can we do better? Even if you didn’t explicitly

set such goals ahead of time, you can still think about your race in

these terms. You can often reconcile your effort in such a way that,

even if you missed goal 1 or 2, you may have achieved something even

greater, although possibly less tangible. Perhaps you learned how to

surge late in a race, finished your strongest last 6.2 miles ever, or

made a new friend during the run. Take it from someone who is too

often too hard on himself – it isn’t helpful to berate yourself

for not achieving some purely arbitrary goal. No matter how you did,

take gratification in your effort.

Set

Your Next Goals

We

marathoners are quintessential over-achievers. We’ve taken the

simple activity of running, something that is generally very good for

us in moderation, and taken it to extremes. Extremes that sometimes

border on being detrimental to our well-being. Most of us began

running for the health benefits as well as the social and

psychological aspects. We’ve taken this to the point where it

drives us, and our loved ones, quite mad.

Goal

setting for activities after the race is best done before

the race. This may involve planning for a second race before you’ve

completed a first one, something most of us don’t do. Presumably,

you had some kind of goal before your previous race, and you at

least, say, completed the race. Now it’s time to set or adjust your

goal(s) for your next one.

The

most important considerations are your own aspirations. If you said

“Never again”, and

still mean it

several days or weeks afterwards, then by all means don’t plan on

any future marathons. Do plan on running, and perhaps racing other

distances again someday, however. Remember: the running part is good

for you.

Time

goals are the easiest to reconcile; you either made it or you didn’t.

On the other hand, it’s been said that the clock will be your most

implacable opponent of all. It becomes excruciatingly clear whether

you’ve met a time goal or you didn’t. Placing and other goals are

a bit more difficult to quantify. Perhaps you may have wanted to win

a small race, but then noticed that Paul Tergat and Paula Radcliffe

had unexpectedly shown up at the start line. This would be a good

time to consider your second or third tier goals. But back to time,

by way of example:

Lets

say that you had a time goal for the race you’ve just completed.

One might be to qualify for Boston with a 3:40 or better, while

another may be trying to break three or four hours. Based on your

training and the timing of the previous race, let’s say you thought

that you could do it. Perhaps you were in the shape of your life.

Assuming you finished, there are three possible outcomes for the race

just completed:

You

exceeded your time goal! All you need to do now is to determine if

you are willing to place the time and effort into further

improvements, or simply assume that you’ve done the best you’ll

ever do, and set your goals accordingly. Changing your goals

completely is worth consideration now – instead of a time goal –

maybe you’ll want to place higher. Perhaps you’d like to

concentrate a different type of event.

You

barely missed your time goal. This means you performed almost as

expected and were on the right track. Many of us have been there:

you were right on pace through, say mile 21, but then the fatigue

caught up with you and your pace slowed. You probably need to only

tweak your training to enable stronger finishes or to correct other

problems.

You

were much slower than your time goal. Even in this instance, there

may have been extenuating circumstances such as terrible weather,

illness or last-minute injury. If, however, there were no such

circumstances, you may need a dose of reality. Perhaps your training

wasn’t as solid as you had thought. Can you train better without

undue risks? Or perhaps this time goal simply isn’t for you; some

people will never be able to run a marathon in that specific time,

period.

Create

a Plan

One

of the important considerations in planning your future running is

the timing. Assuming that you do

want to run another marathon some day, when should that day be? Now

that you’ve completed your marathon, done a post-mortem and set

your next goals, it’s time to create, and then execute a plan. Do

you need to improve fitness by increasing volume or intensity,

maintain your fitness level or simply avoid injury? Your plan needs

to account for it.

Training

plans are ubiquitous. Most are quite good, and work for a variety of

different runners. You need to pick and/or create one that will work

for you, as well as fit into your timing schedule. To help your

planning, reflect on such sources as “Daniels’ Running

Formula-2nd

Edition” by Jack Daniels, “Advanced Marathoning” by Pete

Pfitzinger and Scott Douglas, or Hal Higdon’s Marathon Training

Guide at www.halhigdon.com. Other options are to employ a coach (live

or online) or to simply design your own. To help you with fitting

your training plan into a schedule, I’ve fashioned some for your

consideration.

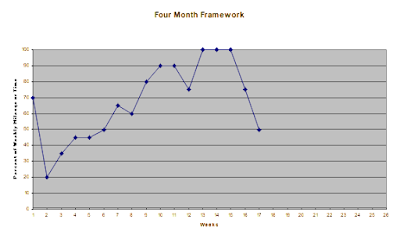

The

schedules are not full-blown training plans. They are the timeframes

with mileage guidelines for your training plans. In terms of

percentage of maximum weekly mileage or time, the schedules will give

you a framework around which to build your plan. They all show a dip

in mileage after your recent marathon and then the build-up for your

next one. The difference between them is that the dip is shorter, and

the build-up is steeper for the four and two month schedules. To use

them, first determine the highest amount of miles or time spent

running per week that you plan to achieve during the training for

your next marathon. Multiply this by the percentages along the

x-axis, and create your schedule.

Six-Month

Framework: Two or

fewer marathons a year – perhaps one in the spring and one in the

fall - work best for most marathon runners who seek optimal

performance. Allowing five or more months between these efforts gives

you the time you probably need to recover before beginning a 16 to 20

week training plan.

Four-Month

Framework: Say you

complete a marathon in May, and want to do another in September. Bear

in mind that the shorter the recovery period, the higher the risk of

injury.

Two-Month

Framework: You run

one marathon, and then need to recover, build up your mileage back up

and taper for your next one, all within about nine weeks. Now we’re

getting really risky, so proceed with caution.

Other

Frameworks: Those

of us who’ve rattled our brains from running too much may try to

run a second marathon less than two months after the first. Some of

us may even run them a couple weeks apart, or, for something like the

Tahoe Triple, only a day apart. Try scheduling rest, build-up and a

taper for that scenario. The truth is that you won’t achieve

optimal performance as well as have the least risk of injury with

anything less than five months time between efforts. This is not to

say that you shouldn’t run marathons more often; if you want to, go

ahead and have fun doing so.

Executing

Your Plan

Lance

Armstrong was interviewed immediately after the 2005 Tour de France

and was asked what he would miss the most in retirement. He probably

thought about the competition, the camaraderie, the overall

excitement. But after a moment’s thought, he said something that

was somewhat surprising. He said, “I’ll never be in this kind of

shape again in my life, and I’ll miss that the most.” When you

think about it, this is a profound and telling statement.

When

you do start training once again, don’t expect to be at the same

level of fitness that you were in during the build-up for your

marathon. Even if the time lapse between your race and your

resumption of training is short, you will notice that you can’t run

quite as fast, long or hard as you used to. This reduction in fitness

should have been built into your new plan, and should not come as a

surprise. Have confidence that your fitness level will indeed return

to, and perhaps exceed, the previous levels.

Since

you’re starting over to some extent, you may actually find yourself

thoroughly enjoying the experience of running again. Whereas it may

have seemed like work whilst in the midst of your hard training, it’s

now become fun again. There is something quite liberating about

running with drastically reduced expectations. Feel free to enjoy the

experience as you did when you first began running.